“There are bugs in my garden!” is usually a sentence spoken with alarm by most gardeners. But what if it didn’t have to be that way? Sure about 1% percent of the invertebrates in our… More

Science Advice from Beyond the Veil

The event was straight out of a novel. There I was, moving my late father’s desk into my home. The desk that had been, in my youth, piled with scientific articles, statistical readouts, and last month’s bills, would now house my own collection of papers along with the memories of my dad. I had emptied the desk of all my father’s possessions before moving it to my house, but somehow I had missed something. As my husband and I struggled to get the desk up the steps, a lone paper fluttered to the ground. I picked it up and trembled as I read the quote written in my father’s handwriting. Despite my attempts at rational thought, I felt like somehow this note had been tucked away for me to find at this moment. I share it with you now, for it contains advice, not only for the making of good science, but for life.

As in any study of nature, so with plant diseases, it is of utmost importance to employ the right methods of investigation, to focus on the matter itself instead of facing it with preconceived notions, and to observe and examine the phenomenon carefully and from all angles. Only an exact and careful study of the earliest and subsequent stages of development can save us from the confusion of opinions and suppositions so prevalent in the field, and lead to valid useful results.

Julias Kuhn, 1858

Thanks, Dad.

Why Vegetable Gardens Are Not Sustainable

Many gardeners, myself included, were inspired to try a hand at vegetable gardening for a combination of culinary and environmental reasons. Nothing can quite compare to the savory-sweet flavor of a sun-ripened tomato; plus, Michael Pollan, and countless other garden writers, assured us we were doing our best for the planet by growing our own. Like other environmentally-conscious gardeners, I researched the best organic soil amendments, experimented with companion planting, and generally agonized over the most “green” way to garden. Over the years, my reading, experimentation, and experience, as both an “almost organic” vegetable farm manager and entomology researcher, have dramatically shifted my view of sustainability. In short, I’ve come to realize that growing produce is never truly sustainable. There’s always a trade-off between conserving one resource and expending another.

I’m not suggesting we should all throw up our hands in despair, or stop trying to garden in ways that are good for the surrounding ecosystem. Some things, such over-fertilizing, inefficiently watering, frequent tilling, and taking a “scorched-earth” approach to pesticide use, are clearly very bad for the environment. However, many things that are touted as “green” are not always what they appear. By understanding the complexity of the system we are working with, we can garden in ways that are more satisfying and steer clear of unscrupulous marketing-claims.

To conserve land, to conserve water, or to conserve energy? That is the question.

When talking about conserving resources in the garden, it’s important to realize that there are biological limits to what you can grow on a piece of land without any additional inputs. Even the most fertile piece of topsoil will be depleted of nitrogen and other plant nutrients after a few seasons of vegetable growing, and the veggies won’t grow, in any season, without a regular supply of water.

Very few of us are blessed to garden on a floodplain that is annually inundated with fresh, fertile topsoil, so if we want our garden to last more than a season, we need to insure the soil is replenished with nutrients the plants need. To do this we can rely on the nitrogen-fixing bacteria that live in the roots of legumes, such as clover, and the natural weathering of the rocks for other nutrients. The cost of this approach is land use, since land being replenished by these natural processes can’t be used simultaneously for growing food. That mean less land for gardening, and less land for wildlife. We could also bring things produced on other land (food waste, compost, manure), and put them on our gardens to supply these nutrients. While this practice gives us more space in our gardens, it just shifts the land cost to somewhere else. This approach is only sustainable if it relies on locally sourced “organic” fertilizers, as the energy cost of shipping such bulky materials from distant sources becomes both energy and land intensive. Alternatively, we could supply our gardens with synthetic fertilizer, which has a very small land cost, but takes lots of energy to produce.

For those of us that don’t have perfectly-timed rainfall throughout the entire growing season (which is most of us), the same kind of trade-offs are involved with applying supplemental water. Traditional dry-land farming techniques rely on wide plant spacing to reduce competition between plants, which, of course, takes up more land. Mulching helps conserve water, but comes with a land cost as well: whatever land the ground-up plants you are using as mulch used to live on. Keep in mind the further away you source your mulch, the more energy it takes to get it to your garden. Irrigating your garden gives you more reliable results than relying on rainfall, but the equipment and pumping water add to the energy cost. In greenhouses can you to grow a ton of veggies in a small space and they are extremely water efficient, but both the construction and maintenance of a greenhouse are energy intensive.

So what is an environmentally-conscious gardener to do? Maybe we are asking the wrong question. Instead of asking “Is this gardening practice sustainable?” we should be asking “What resources do I most value conserving?” and “What resources are less limiting to me?” For example, if you live in an arid climate, you might want to use heavy mulches, rain water catchment, and wide plant spacing. If you are a city dweller with a postage-stamp yard, you might want to grow intensively in irrigated, raised beds or a small greenhouse. If you live on wide, rolling pastures, you may have the space to rotate produce with legumes or small-scale livestock production. You may even decide that you want to just grow a few of your favorite veggies in pots near the house, and turn the rest of your yard into a vibrant wildlife garden.

While there are no paths to completely sustainable vegetable gardening, there are many ways to garden that preserve what we value. And that’s ok.

The Hidden Dangers of Botany

Pursuit of botany starts off innocently enough: maybe you are a gardener interested in learning about plant biology, maybe you are a survivalist wanting to learn about edible plants, or maybe you are a wildlife lover who wants to attract hummingbirds to your yard. Whatever the reason, you need to make sure you are fully prepared for the havoc you may wreak upon your life. Before you read that gardening book, click that link, or go to that native plant conference, take the time to educate yourself about the hidden dangers of botany:

- You can’t un-see the scenery.

Like walking in on your parents, plant identification is one of those things that you can’t un-see. Before you learn about botany, the world around you consists of only vague categories of greenery. Afterwards, plant scientific names practically scream themselves at you every time you go outside. Sure you might feel “more engaged with the natural world” by knowing how to properly address the surrounding flora, but once you learn those names, you will never be able to traverse the countryside in blissful botanic ignorance.

- You increase your risk of accidents.

Your new-found plant identification skills will also put you at greater risk for bodily harm. You may skin your knees while climbing logs to photograph ferns. Wildflowers off the side of the road may catch your eye and cause you to swerve your vehicle dangerously. Even on the water you are not safe. Plants along the water’s edge will call you like sirens, and threaten to entrap your kayak on snags.

- You will start to hoard plants.

Each new group of plants you learn about will become The-Most-Awesome-Plants-Ever and lead to a cycle of never-ending garden expansion. Sure gardening is great way to exercise in the great outdoors, but you will always be tortured by the desire for “just one more plant.”

- Your relationships will be strained.

Once you learn a bit about botany you will want to share some of your knowledge with your friends and family. Occasionally, you may wow them with fun facts about some unusually useful/poisionous/carnivorous plant, but most the time you will simply become a source of exasperation. Your friends will roll their eyes as you point out (yet another) wildflower on your walk together, your significant other will sigh as you bring home (yet another) species of plant to add to your over-brimming garden, and your kids will become annoyed that (yet again) you are taking so long looking at all of the plants. While vacationing, more fun loving people will want to go to overpriced theme parks, but you will be torturing your family and friends by suggesting (yet another) trip to a botanic garden.

- You will want to learn more science.

Botany is the ‘gateway science’ to obsession with a wide range of natural sciences. Once it has you in its clutches, botany may start you off on the path to wanting to learn entomology, ornithology, or, Lord-forbid, mycology. It may even send you off into the esoteric realms of soil chemistry or meteorology. The madness will simply compound itself.

If, despite all these dangers, you still want to pursue botany, go right ahead. Learning botany may indeed help you grow prize-winning dahlias, get free food from your yard, or become a better steward of the earth. Just know what you are getting into, and don’t say I didn’t warn you.

How to Get a Kid to Garden: Minecraft Style

Once, before being corrupted by his video-game obsessed peers and his parents’ too lax “screen-time” rules, my son actually enjoyed gardening. He would toddle around after me planting seeds, watering plants, and picking any tomato that showed the slightest hint of redness. At one time, he knew which plants in our garden were edible better than most adults. Now, my son accuses me of having too many “useless flowers” in my front herb garden. Determined to help my son recapture the love of gardening, I gave him a sales pitch I knew he could not refuse: “We’re going to make a Minecraft garden.”

Project 1: Failure in miniature.

My first plan was to take some old boards from discarded bookshelves and use them to build a combination sandbox and raised miniature Minecraft garden. I made a terraced “hill” out of scrap 2×4’s and used a cement mixing trough we had lying around for a “lake”. My son and I built and painted a “Steve” character, villager, ocelot, and cow to inhabit it.

On the plus side:

- My son got to practice carpentry skills building the frame and figures with me.

- Painting the little figures was a fun diversion on a day the power went out.

- Frogs love the little pond, and we have tadpoles every summer.

On the minus side:

- My son was slightly too old for the sandbox and has used it exactly once since we built it.

- My son complained early on that the garden “doesn’t look enough like Minecraft.”

- The Japanese holly bushes I planted as “trees” got way too big before the ground covers filled in, and had to be moved elsewhere. The tiny dwarf boxwoods I got to replace them are definitely “slow growing” as advertised, and my son will probably be in college by the time they get big enough to look like miniature trees.

- I chose my main ground cover poorly. The Irish moss looked lovely in the pots at the garden center, but it was not happy in our sultry Carolina summers. The first year it sat there and glowered at me. The second year it shriveled up and died. I replaced it with a fast growing sedum, which I should have done from the start.

- The whole thing takes an insane amount of weeding and trimming for the tiny space it occupies.

- I think the bookshelf boards we salvaged for it were originally painted with oil-based paint. The green we painted over them started peeling off after a few months.

- I neglected to put waterproofing sealant over the paint on the figures, and the paint-job on them is rapidly deteriorating as well.

- Neither my son, nor I like to weed it. The results are what you would expect.

Project 2: If at first you don’t succeed…

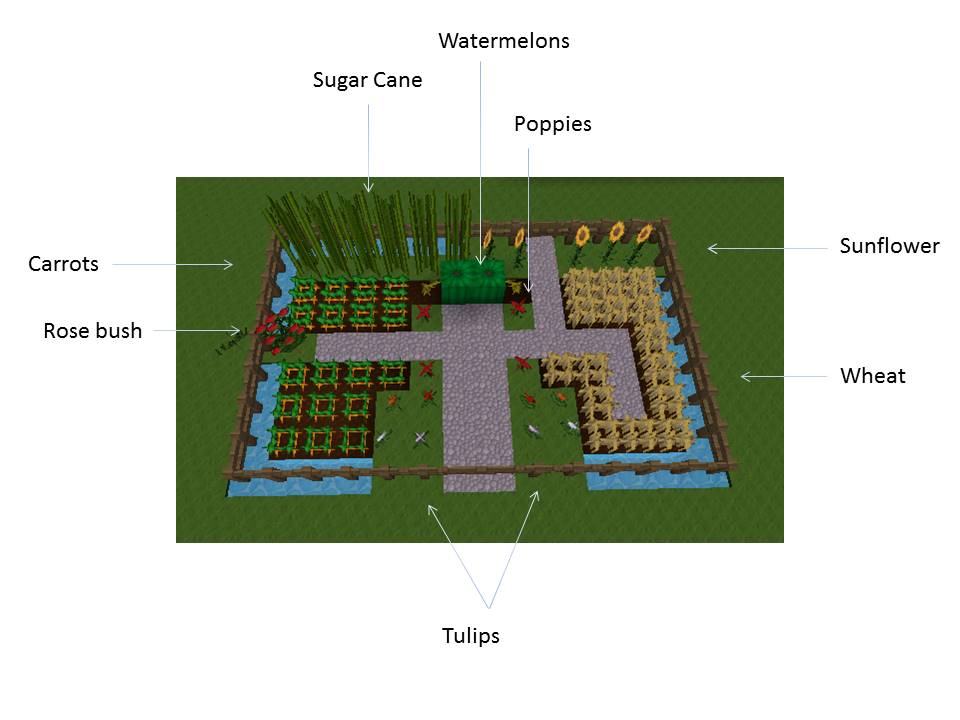

After the failure of our first attempt, my son surprised me by lobbying to try again. He said he wanted to try growing the real versions of plants he commonly grew in his Minecraft game. As I wanted to expand my vegetable garden anyway and was still trying to find a way to bring him back into the gardening fold, I agreed to his plan.

The second attempt was much more successful. The poppies and some of the sunflowers were no shows, but the rest of the garden grew beautifully. Although my son sometimes grumbled about helping me, he dug, planted, weeded, and harvested with me. Looking back, he claims he actually enjoyed some of it.

In Minecraft, all flowers bloom all the time, and wheat goes from seed to harvest in about 10 minutes. In real life, my son and I watched the garden unfold over the course of the season. I’m sure when he’s 30 he’ll also value the educational aspect of that.

Did these projects cure my son of his screen obsession, and give him back the gardening fervor of his toddler-hood? Hardly. Were they an enjoyable pastime for the whole family that got us all out in the garden? Definitely!

Odorous House Ants: The Ants We Gave Superpowers

Odorous house ants are near the top of the list of America’s Most Unwanted Insects. Although scientists commonly refer to them as Tapinoma sessile, most people know them as ‘sugar ants’, or more colloquially, ‘piss ants’. By any name, they are the plague of many an American kitchen from the east coast to Oregon, and, as such, most of the research on odorous house ants has been devoted to figuring out how to kill them.

There are actually several species of ants around 1/8” long that are lumped into the ‘sugar ant’ category of home invaders. Odorous house ants can be distinguished from the rest of them by their uniform dark brown color and, as the name implies, by their distinct odor. My colleagues Adrian Smith and Clint Penick have published an amusing study that claims the odor is akin to blue cheese, but I would counter that the smell is more similar to slightly rotten citrus. Either way, once you have a wiff of these ants, you’ll never forget them.

Neither their home-plaguing habits nor their pungent chemistry is what inspired me to study odorous house ants for my graduate research. I was more interested in understanding their ecology. Why? Because something about living near humans gives these ants superpowers, and I wanted to figure out what.

When odorous house ants live out in the woods away from urban areas, they are the ant equivalent of the wimpy kid on the playground. Their colonies are small, maybe a few hundred individuals. Many times they have only one queen, but sometimes they have a handful of queens. If some odorous house ant workers find a tasty dead bug and another species of ant comes along, the odorous house ants usually end up losing the fight for the food and running away.

However, when odorous house ants end up in urban areas, it’s like the wimpy kid suddenly drank Extra Strength Super Power Juice. Odorous house ant colonies in cities grow to millions of workers in size with thousands of queens. Such large colonies form by smaller colonies budding off of the founder colony over and over until there are huge networks of nestsites where the ants freely exchange queens and workers. These so called “supercolonies” can function over an area of several city blocks. Moreover, unlike in rural settings, these city-savvy ants tend to win fights over resources with other species of ants.

So what causes the change?

I thought it might be the way we modify the landscape around our homes, so I set off to do a survey of 24 urban and suburban yards looking for odorous house ants (and other urban ants). I trapped ants in the yard, near the houses, and in garden beds away from the house. I measured how thick the vegetation was, what the ground cover was, recorded the dominant plants, measured the amount of shade, and measured how deep any leaf litter was. Because odorous house ants prefer to live under preexisting debris, I counted the number of potential nesting sites such as mulch, logs, rocks, and landscape timbers near where I trapped ants.

Like many ecology research projects, I discovered much of what I spent long days meticulously measuring in the hot summer sun (while pregnant!), didn’t have any measurable relationship with odorous house ant numbers. However, a few things did correlate with more odorous house ants being present: leaves, logs, and being close to the house. What does this correlation mean? Well, because this was just a survey and not an experiment, I can’t claim that any of these things cause higher number of ant, just that they might be related. Maybe it means that odorous house ants do well in urban areas because they have more nest sites, or maybe our homes simply provide a convenient source of food or warmth. More research involving actual experiments would need to be done to see if any of these potential causes are indeed the case.

Since my project, other researchers have continued to investigate the source of these ants success. Adam Sayler and his associates, did surveying work of ants in natural, semi-natural, and urban areas that suggests that odorous house ants may be helped by the fact that human disturbance is bad for other species for ants. In short, odorous house ants can handle the bustle of the city, their competitors cannot.

Although not explicitly about ants, research coming out of my colleague, Steve Frank’s, lab has shown that tiny, tree sucking critters called scale insects, are more abundant in cities due to urban warming. These insects secrete a sugary solution called “honeydew” that is used as a food source by many kinds of ants. During the course of my research, I noticed huge trails of odorous house ants going up and down trees, presumably collecting honeydew. Maybe the urban “hotspots” for scale insects, are helping fuel the massive colonies of odorous house ants.

Whatever the reason for their urban superpowers, it isn’t something that has happened just once. Sean Menke and his associates found that many separate groups of odorous house ants have evolved the ability to make supercolonies in urban areas all over the US.

So is it shelter, response to human disturbance, or heat-loving food sources that turns these ants from wimps to supervillains? In all actuality, the secret to odorous house ant success is likely a combination of many of these factors, all of which are in some way related to the way we build our homes and maintain our yards. So the next time you grumble at the line of ants traipsing across your kitchen, keep in mind that these creatures may somehow be a monster of our own making.

Would you play Pokemon Go for science?

My son and husband have just returned from a pleasant walk around the neighborhood during which they managed to snag a Charmander, Spearow, and Scyther. They will now take these creatures home to care for them, train them, and watch them develop. This is, of course, not wildlife biology, but the game Pokemon Go, and it could be the start of something revolutionary for ecological research.

For those of you not familiar with the Pokemon mania that is sweeping through the population of Millennials and their progeny, this newly-released augmented reality game transforms Pokemon from something played on a screen to a real-life search for virtual creatures that can only be found by walking around outside. To play, you actually have to go out in your yard to find grass-type Pokemon and go to the park with a pond to find water ones.

Many elements of Pokemon Go embody the things that I love about my job as an entomologist: going outside, looking for creatures, collecting them, bringing them back to learn about them, and sharing my discoveries. Unlike the average Pokemon hunter, I don’t make the insects I bring back to the lab do battle with each other; however some of my colleagues who study ant behavior do.

The similarity of Pokemon to entomology is no coincidence, the game designer, Satoshi Tajiri, was an avid insect collector as a child, and the whole idea of battling creatures was inspired by the Japanese pastime of beetle battling.

Even as I am struck by the similarities between of Pokemon and my profession, I am enthralled by the idea of developing a similar game that takes Pokemon Go’s photographic creature-hunting approach to “collect” real organisms as part of a massive citizen-science based ecology project.

In my imagined game of ‘Ecology Go’ (please help me think up a catchier name) users would be sent to “scan” various birds, beasts, and bugs by photographing them with their phones. Once scanned the user could get a cutely-drawn virtual “copy” of said creature to care for in a little electronic world on the user’s phone. Such creatures would need virtual food or shelter which could be obtained by photographing real-life trees, flowers, and other host plants. Of course, in addition to being fun, this game would be stealthily educational, teaching people how identify the living things that surround them, but don’t mention that part to the kids.

Meanwhile, the information from the photographs could be used by scientists interested in ecology and biogeography (the science of what organisms live where) to answer questions about how well pollinators are doing, where birds are migrating, when pests are spreading, and how all these things are impacted by land use and climate changes.

In a highly unscientific survey of user acceptance, I have run this game idea by an actual 10-year old, who said that my game idea sounded “fun to play” and who offered helpful suggestions such as “make it so you can build things for your virtual creatures” and “include slimes and dragons.” Several 30-year olds have mentioned that they would want to play too, but as all of them were biologists, take the interest level of that demographic with a grain of salt.

Although I know that image-recognition software isn’t yet up to snuff for a ‘Ecology Go’ game to exist, such a game is not so far-fetched. Apps, like Birdsnap, are working to improve upon machine recognition of birds from photographs, and citizen science apps such as, the Lost Ladybug Project and eBird, already help scientists track the numbers of rare ladybugs and birds. While we wait for machine learning to catch up with human visual acuity, anyone who takes a screen shot of an interesting (real) creature while playing Pokemon Go can put it on Twitter with the hashtag #pokeblitz for scientists to identify. Perhaps, the closest thing on the internet today to “Ecology Go” is Project Noah an app which gives users missions to photograph different types of plants and animals around them.

However, none of these apps and projects have the game mechanics that would give them widespread appeal to those who are not already biologically inclined. Pokemon Go is fun because it turns your yard and neighborhood into a daily scavenger hunt. Like the way my research provides me various incentives to collect a ton more insects that I would do on my own, Pokemon Go provides incentives for users to keep Pokemon-hunting for longer than the average person would casually search for wildlife. An actual game-based ecology app would have the potential to connect its players more deeply to the natural world, and at the same time, give scientists the information they need to understand that world more clearly.

Dad’s Garden: A Garden of Memories

This blog is intended to be a place of lighthearted, nerdy gardening ideas and fun science information. However, on the anniversary of my father’s death, I’d like to start it off with a more serious dedication:

My Dad was many wonderful things, a research scientist, a dedicated parent, an avid naturalist, but he was a lousy gardener. While my mom filled the yard with overflowing beds of stunning ornamentals, my Dad lay claim to the dry, root-choked bed under an enormous weeping-willow tree in the back corner of the yard and attempted to grow the flowers he truly loved, woodland wildflowers. The garden wasn’t quite a total failure. I remember him proudly naming to me the few scraggly plants that survived in the outskirts away from the willow’s densest roots, mayapples, violets, and for a time, bleeding hearts. Those poor bleeding hearts; they weren’t happy under that tree, and after it was cut down to make way for a sugar maple, they were equally unhappy in the baking sun. My Dad’s attempt to replant the bleeding hearts in the shade closer to the house only resulted in their untimely demise under the careless feet of my sister and I. However, for the brief years they were alive, I remember being utterly enchanted by the complex shape of their delicate flowers.

Despite his failure as a gardener of wildflowers, my father was wildly successful at sharing his love of botany with me on the hikes we had together in my early childhood. He would constantly point out any, and every, wildflower we came across, he would wax poetic over the blooms of flowering dogwoods and redbuds in the spring, and he would even exclaim with delight at obscure liverworts we saw while climbing over mossy rocks along streambanks. I’m sure that these formative experiences were a large part of what drove me to become a biologist later in life.

My father’s will stated that, upon his death, he wanted his ashes scattered where “green thing grow and waters flow”. Most of his ashes have been dispersed in the waters he loved, but I brought a few home with me because I felt that he needed a second chance at the wildflower garden he always wanted, but never had the time, or later in life, the energy, to care for. I scattered a few ashes in shady garden bed, and planted a redbud seedling I that had volunteered in my vegetable bed in the center of the new bed. I am slowly filling in the remaining area with wild flowers: mayapples, wild iris, columbines, solomon’s seal, spiderwort, foamflower, and of course, bleeding hearts. One of the bleeding hearts I planted did not survive the winter, and another got smothered by my overly-zealous mulching. Even in death, the man has bad luck with bleeding hearts. Fortunately, the rest of the plants seem happy. Although the garden currently has the rather awkward looking “new garden” syndrome, my hope is that as it grows into its own, I will have a nearby place of natural beauty for reminiscence and solace.

I close this post with a poem I wrote for my Dad’s memorial service. If he were alive, he would have embarrassed me by sharing it with all of our family and friends. Since he is gone, I guess it is up to me, in many ways, to carry on his work.

A Poem upon the Death of My Father

There is no poem to read upon the death of my father;

No Longfellow can quite express the luster of his greying hair,

His faltering step,

The twinkle in his eye.

There is no poem to read upon the death of my father;

No Frost can capture his love of the dogwoods in full bloom,

His rambling tales,

His smile now gone.

There is no poem to read upon the death of my father;

No Dickenson portrays the emptiness of his flannels shirts,

No Whitman tells of days of constant measuring,

No Keats depicts his gentle laugh.

There is no poem to read upon the death of my father;

The best they do is fail to say the inexpressible.

Introduction to the Biologist’s Garden

There are a ton of biology blogs and a multitude of gardening blogs, but few that seem to link the two together in a way that is satisfying to me as both a biologist and gardener. Garden Rant and the Biology Professors are on the right track, but deal mostly with horticultural science. Your Wild Life is a great place to learn about the ecology of humans and their houses, but what about garden ecology? The Artful Aomeba is a treasure trove of the wonders of natural history worldwide, but I want to focus more on the natural history of the little guys in our own backyards that go unnoticed. Most of all, I want everyone to feel like biological science is for everyone, accessible to anyone with a yen to grow, observe, think critically, and discover things. I currently envision the blog to have four main areas of focus:

- Occupy Biology: 1% of the species in your yard get all of the glory. Discover the amazing hidden lives of the other 99% of living things that surround you.

- Sustain-A-What: Make the link between nutrient cycling and fertilizer use. Learn more about who’s eating whom in your garden’s food chains. Enjoy applied ecology for gardeners.

- Geek Out: Are you obsessed with science, history, video games, or books? There’s a way to geek out about that in the garden. Check back to this page for inspiration for theme gardens to match (almost) any obsession.

- We Can Do It: Biology is for everyone! Learn how to set up experiments and participate in citizen science projects (or start your own!). Have fun doing biology in your yard.

As a full-time research associate in an agricultural entomology lab, I may be a bit slow to post during the peak of my summer research season, but I hope you will follow me on Twitter to get updates when I do. This blog will be a fun place for biology nerds to learn more about gardening, gardening nerds to learn more about biology, and everyone to become a little of both.

Hello world

This is just a test post for setting up my blog. Enjoy this picture of a Lego smiley face.